As I wait the timeless void that publishers use to respond to authors, I offer to you the second chapter of my novel.

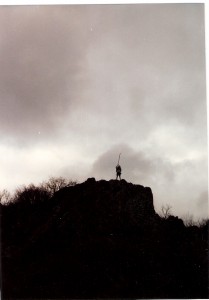

Everyone has a special place, inside or outside, that makes them alive again.

Chapter 2

“Is there a big moment you had when you thought you needed to do this?” Mara was on the loveseat with a glass of wine, and her legs were off to the side as she sat on her hip.

Don went to the place that conversations like this drove him to, where he allowed them to. He looked out the window of the living room in his house while he reclined on the couch and held a glass of beer.

His lips squeezed together and drew a grim line as his eyes held a sparkle. He never gave up on things even when they didn’t make sense and he knew that tenacity alone would get him somewhere. He never knew exactly where, but, if he got there by toughness, it would be worth going to. He heard Mara’s muffled talk in the room but he didn’t come back for a minute.

He needed that time to study the trees, high up where the thin twigs shot off the branches that should have been removed, but looked so good and finely articulate against the blue sky. The brighter the sky, the better those little branches looked, Don thought, even if they were dead up there and needed to be cut off. He admired how they looked right now, and every time he needed them to be there—when he had a drink and needed to stare at the trees in the sky outside.

“I can’t nail it down to one thought, or one time when I sat there and said, ‘yeah, okay, now I know everything.’ I’ve just been thinking about what the most important things are, and how well I know myself.”

Mara took a sip and looked at him.

“What kinds of things are you talking about?”

The sound of steady traffic on the highway made a dull whoosh that sounded like heavy gusts of wind before a rain shower. Don listened to this, and could hear the robins chirping when it was at its quietest.

In the near silence then, a rush of emotion and vision from his childhood came over him, mixed with an ache that had always been melancholy. It felt like purity now. Don saw in that moment that he had been having genuine dreams and his idea matched up with what he should do.

He knew that the attempt at describing the flood of thoughts would be useless. Some things only have meaning inside of themselves.

As if the explanation were right behind the door, Don twisted his neck to look at the closet, and said, “I think I left something in the West that I need to get back. I don’t know what, but I’ll know it when I see it.”

Don glanced at Mara. She was looking out the window.

“I want to start by going to places I remember my dad taking me to as a kid.” He turned his head again to look over the front porch and above the neighborhood houses. In his periphery he could see the pamphlet on the end table that Mara had printed for him a few months before, when his brother had been diagnosed. All the other colors of the living room seemed to melt now into the gleaming white of the top page, to which Don finally switched his eyes. In his head, he made out the bright crimson letters that read: Living a Fuller Life with ALS.

“I’ll trust the way to reveal itself to me when I get there. This is unreasonable, I know, but this thing is like a survival instinct. The deepest things in me tell me the truth, I think, and I do them. That’s what this is. I know I can get on some kicks. Do you get a feel for how this is hitting me?”

Mara smoothed down her hair and rested her hand in the crook of her arm. “Yes, I see it’s affecting you. I guess…I’m sorry. I’m not trying to ignore anything you’re going through, but you have to admit, Don, that you’ve gone through all sorts of phases before, and a lot of them seem to settle down after awhile.”

“If this were a phase I’d know what you’re talking about.”

She put her hand out and the corners of her brows dropped down. “I’m not saying that. And I’m not necessarily saying not to do a trip. But do you see what I’m saying? I think we both go through times where we get excited about something, something that sounds totally different, and something that will let us feel free for awhile.”

“That’s what I’m saying. That’s what I’m talking about. Freedom.”

“I know you’re talking about freedom but I’m talking about reality. Look, I understand what your idea is, and it’s a good one. This sounds like something you need. And to tell you the truth, I’m almost glad you feel it, because I know that thinking about a change of pace is helpful for you.”

“Right, but I’m saying not just thinking about a change of pace, but changing it, doing it. I’m so sick…”

“Will you let me finish?”

“Go ahead, finish.”

Mara tilted the empty glass with her wrist to accentuate her words. “If you’re set on doing it, and you really think it’s right, I support you.”

Don slowly stood up. He flicked the globe of his glass with his finger. “I don’t want to just run off. I don’t want to just dump all this stuff on you and go.”

“I’m not worried about anything being dumped on me.” She craned her neck forward and nodded. “I want to make sure it’s the right thing to do now.”

Don took a deep breath and chewed on the inside of his lip. “I believe it is.”

“Okay. Then do it.”

“I know you could flip out, and this is irresponsible, and we don’t need this right now. But it’s grabbing me. I don’t want to get all out there about it, but I feel like I’m touching the pulse of the world or something, the part of the world that’s for me—but there’s a blanket over it so I can barely feel it. There’s something heavy on me. It’s faint, but I feel it and it’s real.”

Don sat down again, on the edge of the couch.

“In the Black Hills there’s this private property cow field where my dad and I fished when I was in high school. My dad’s old friend Bob was with us and he knew the area since he’s from there.” Don’s eyes were fixed on the wall as he told this, trance-like. He felt what it had felt like to be fifteen and there, and in high school, and to love books, and to not know many things yet.

“We went back to this little motel in Spearfish, and ate the trout. The rooms were like cabins, or my grandma’s house, with wood paneling and old linoleum. I remember Bob saying that his mother had always served white bread and butter with trout because, if you got a bone caught in your throat, the bread would help it go down, if you choked.”

Mara knew how Don was when he was telling a story. He leaned back into the couch as he spoke, and looked at the edge of the carpet where it met the wood floor. Mara watched Don and listened.

2 Responses to Highway Bleeding, Chapter II